The Single Question That Changed My Life

And saved millions of others

The question was straightforward: Of the 3,811 patients with tuberculosis diagnosed in New York City last year, how many did you cure?

I was half a year into my role as the head of the New York City tuberculosis control program. The previous night, Dr. Karel Styblo had taken our annual information summary back to his hotel to study. I thought it was a good report. I was confident. But the next morning he pointed out several epidemiologic trends I had missed. This was galling—I had written the report! Then he asked me that question, and I didn’t know the answer.

I was terribly ashamed.

The report told him all about the people we diagnosed and treated, but it didn’t tell him how many of the patients with tuberculosis we’d cured.

This question—How many did you cure?—changed how I’ve thought and worked ever since, and it holds the promise for an approach that can transform our expensive medical care system from sickness care to health care.

Dr. Karel Styblo and his Approach

Dr. Karel Styblo is one of the most important scientists you’ve never heard of. He understood tuberculosis profoundly.

Styblo learned to orchestrate all three parts of the formula. He saw invisible trends and established the concept of a technical package based on scientific and practical rigor that I explore in my forthcoming book.

Styblo’s laser-like focus on outcomes underpinned all of his work. He developed a system for tuberculosis control, known as DOTS, that consists of five components.

Political commitment. Enough money and staff.

Good quality diagnosis. Know who has the disease.

Reliable drug supply. Have drugs that work well.

Good quality treatment. Make sure people take their medicine. (This is especially important when you deal with an infectious disease. See last week’s column on the apostle of treatment observation.)

A powerful information system. Be accountable for the outcome of every person diagnosed.

For many health problems, the Styblo approach is the only accurate way to determine and improve quality.

Styblo explained, “Tuberculosis control is really very simple. Just one rule: No cheating. Every patient in your area, you are responsible for their outcome.”

This approach is at odds with that of many doctors, nurses, hospital administrators, and political leaders who focus on the patient or voter in front of them, not the actual outcomes of all people in need. Clinicians may be oblivious to the patients who stopped treatment or never started it. Complete prospective cohort evaluation—tracking the outcomes of every patient—is a simple approach to make the invisible visible. It holds a key to improved health care.

Tuberculosis in New York

The day after Styblo’s visit, we began reviews of every cohort of patients, in every part of the city, every quarter. One researcher used Styblo’s method to track patients after hospital discharge and found that the program cured only 11 percent—the rest were either lost to follow-up or dead.

We had a tremendous amount of work to do.

I left these initial cohort reviews nearly in tears, as did other leaders and staff. The situation seemed hopeless. But then the teams did whatever it took to get treatment to patients.

Outreach workers went to park benches, homeless encampments, abandoned buildings—anywhere to help patients with their social needs and give them treatment. These frontline heroes were instrumental in the reversal of the tuberculosis epidemic.

Cohort reviews revealed many problems. These ranged from outreach workers who needed cars to visit patients who lived far from public transport, to overcrowded clinics where staff treated patients rudely, to private doctors who prescribed the wrong medications. Solutions to these problems were sometimes complex, but the bottom line was simple: Every patient. No exceptions.

The review of every patient forced the program to address each problem systematically. At the next quarterly review, we would see if our solution had worked. If it had, we congratulated and encouraged staff. If it hadn’t, we looked for new ways to solve hard problems.

And now the answer to Styblo’s question is that, from far less than half when he visited, New York City has for many years cured nearly all tuberculosis patients.

The Questions We Ask Matter

All too often, programs fail to look at rigorous outcomes. They miss this obvious but essential information in a blizzard of data. Styblo saw the essential truth that the most important fact was not the number but the proportion of all patients cured.

Some people say we should do everything to address a health problem. But we shouldn’t do everything. We should do the most important things that help the most people. We need to scale what works.

In a future column, I’ll outline how the failure to think in terms of outcomes is condemning millions of people around the world to avoidable heart attacks, strokes, and death at a young age.

Dr. Karel Styblo understood this, and the system he developed has successfully treated more than 40 million people with tuberculosis.

Styblo’s approach can transform far more than the tuberculosis treatment. It can be applied to the treatment of hypertension, HIV, hepatitis, depression, and more.

Regardless of what we treat, we need brutal honesty about how well our treatment programs are doing. We must ask the right questions and remember that the goal is not to get the most people into treatment, it’s to get the most people treated effectively.

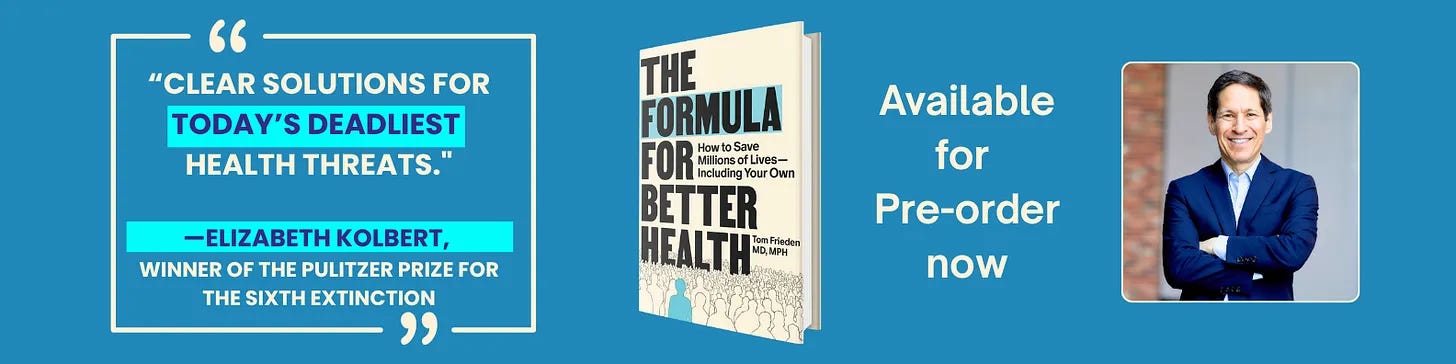

Dr. Tom Frieden is author of The Formula for Better Health: How to Save Millions of Lives – Including Your Own.

The book draws on Frieden's four decades leading life-saving programs in the U.S. and globally. Frieden led New York City's control of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, supported India's efforts that prevented more than 3 million tuberculosis deaths, and led efforts that reduced smoking in NYC.

As Director of the CDC (2009-2017), he led the agency's response that ended the Ebola epidemic. Dr. Frieden is President and CEO of Resolve to Save Lives, partnering locally and globally to find and scale solutions to the world's deadliest health threats.

Named one of TIME's 100 Most Influential People, he has published more than 300 scientific articles on improving health. His experience is, for the first time, translated into practical approaches for community and personal health in The Formula for Better Health.

I have lost interest in this column because it is too focused on Dr. Frieden and not enough on patients and healthcare in general. So, I have unsubscribed.